Agile teams, or teams that have recently adopted Scrum, face a lot of challenges on their journey. Imagine for a second that they have adopted the framework one year ago, have standardized the known agile practices and mindset, and are somewhere between “norming” and “performing” stage(Tuckman model, 1965).This leaves us with a lot of space for improvement.

Having in mind adoption of Scrum does not necessarily improve all the processes, behaviors and strategic acumen in a company or project team. I would like to share about a change journey story for two teams who have achieved the above, and they’re still struggling with additional problems, such as for example:

- Poor understanding and sense of urgency from the delivery management

- No willingness to stand up for the teams

- Harder communication with other distributed teams

- No relevant feedback from delivery management regarding the biggest problems about product improvement, delivery improvement and client communication.

At that time, I saw an urgent need to take several courses available in the company related to change management, and I tried to familiarize myself with John Kotter’s framework for change:

We organized a two-day training for the affected teams, and made sure that it did not adversely impact their scope nor their delivery. At the time, I was very close to my pregnancy leave and I was even more eager to make sure they understood what they were going to receive from this training… additional knowledge that would help them move towards positive change and resolve the lingering problem.

I was anxious to make sure they could successfully address the change they wanted to see in their current project. They were all a fantastic group of developers, QA, solution architects, etc. What they lacked was proper change management experience to help them solve these problems. After successfully attending the training on John Kotter’s powerful principles for change, we opened up several discussions.

We were talking about what would be the best to do, in order to create a powerful change plan. We started with Creating a Sense of Urgency.

We all voted our solutions architect as one of the most respected people on the team, to email our delivery manager and add our branch manager in the loop.

What we got was neither success nor failure. We received a vague response, as we expected. It was full of resistance to changing her behavior, with little commitment to effort, and no mention of the reasons why our delivery manager’s behavior was the way it was. But not everything was adverse, we certainly did something great…. we raised attention to our general management. This was the key factor in us not giving up. Our following step was to make sure we create a Guiding coalition. It was the key people in our teams who stood behind this change initiative.

Our third step was to form a Strategic Vision, we made sure we didn’t stop with the first email communication, and we followed that conversation and continued to talk to our branch manager about the persistent problems, as well as the zero trust derived from our delivery manager. It was a difficult game to play during a period of time when the scope was tight and no delivery or process alterations were allowed.

We quickly listed our Volunteer Army. It was our Solution Architect, our tech leads and our branch manager who joined our “troops”.

We removed barriers. We managed to enable action by speaking to all our members, and making sure we are all on the same page. We were also making sure everyone in the teams wanted to achieve the same thing.

Getting a better delivery manager to support us and make sure that we were heard, listened to, and can be trusted for all actions towards the customer relationship. Our teams were glad at the time… a few months into the change plan. They managed to have more than one conversation with the company’s executive team and with the customer. Both parties were completely dissatisfied with this important function.

Small, SHORT-TERM wins were visible on the horizon.

Sustaining acceleration wasn’t easy. I was already way out of context, on a pregnancy leave.

We had to sustain the acceleration of this change journey for the betterment of our teams. Group members met regularly in their retrospective meetings, and discussed next actions, keeping the status active. Finally, after 7 months of constant negotiations, emails and online conversations, the decision was arrived. Teams would get a local delivery manager who will be physically present, be listening and able to stand up for our teams. It was official. There were no teams happier than mine at that moment. I said to myself… thanks to John Kotter.

And Time flew…

I recently had the intriguing opportunity to join a new educational body in the field of change management and Enterprise Agility. Having completed the certification, and gone through many examples of implementation, I can quietly say that the program offered a wide palette of change management techniques. As a set of tools to cope with change, whether in traditional, classic agile adopting or exponential enterprises.

I have become familiar with a different tool for change called the Change Journey Pyramid. (Bühler, 2018)

The first thing that came to my mind was: what if I had this tool available back in 2017? How would I use it?

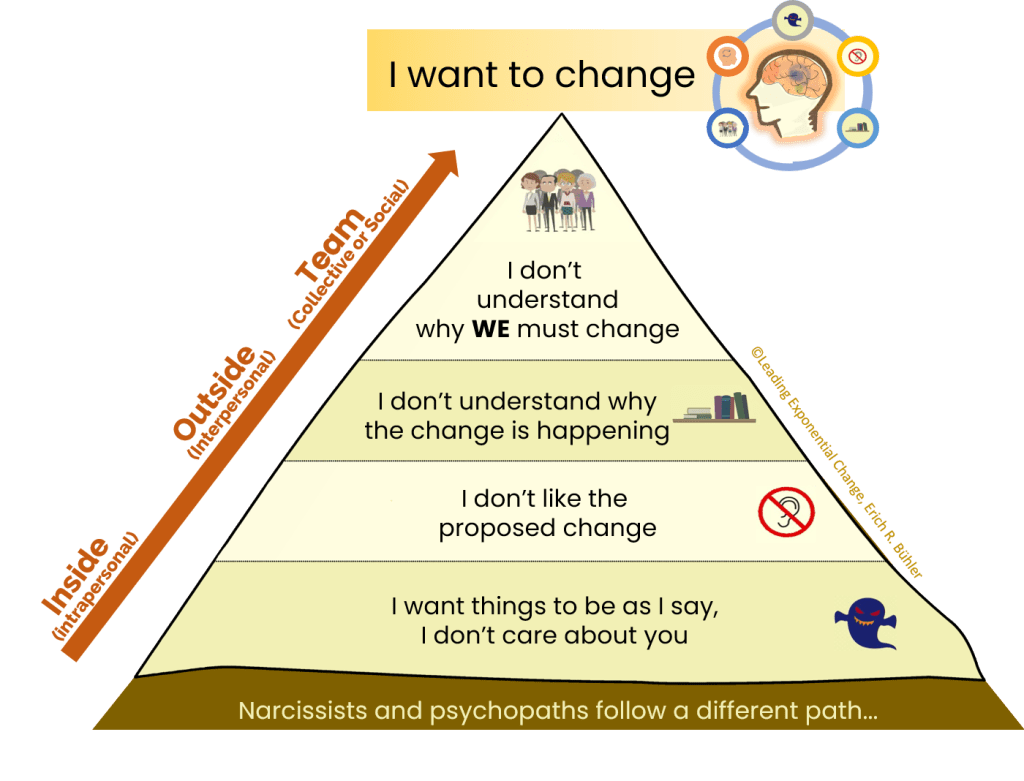

The bottom of the Pyramid of the Change Journey starts with the people in a company who are least prone to change. As was our lead delivery manager.

He was sure he was doing the right thing and didn’t even think about why he was reacting that way. Most of the time he expressed his opinions as “I don’t want to change, I don’t care!“. He was not even aware that an important part of his brain, the amygdala, which controls unconscious fears, including the fear of losing prestige or power, was affecting him.

Undoubtedly, he was at the lowest stage of this pyramid. At that time we had no knowledge of these kinds of tools, so we didn’t know how we should talk to him, face to face, or get him to be in our facilities as little as possible.

The following stage was one where we were constantly faced with “I don’t like this proposed change.”

It seemed that this person did not understand that he was moving through the lower levels of the change journey pyramid, and at the same time, he did not realize that he lacked knowledge of why he needed to change.

We didn’t know either, so we didn’t use any of the tactics to take him through the change journey we wanted. The following stage that we could see that was happening for this person was: I don’t understand why the change is happening.

It was clear for us he didn’t have enough knowledge about the most important issues in his job. He had no communication skills for our team, no negotiation skills for our customer. In fact, we felt that the real issues affecting us were not being solved.

We had to constantly adjust our scope as all the features were high priority and all were urgent. We realized that many were not so important. We tried to manage prioritization, but lacked a capable delivery manager. In the end, we managed to switch to Kotter’s way, which was a more drastic way of solving things. We didn’t even get to the: Why must we change?

He was not aware of the word “WE” when talking to our teams. One thing was certain… we wanted to change him quickly.

This is my personal story about a model applied when we didn’t have enough knowledge of how another model might work and might cause less drastic and painful results for all parties to a problem.

It is always important to think hard about the change you would like to see in any of your teams, processes, and the whole organizations. It is important to understand, reflect, align with the opinions and ideas of your team members and then act. Whether you use John Kotter’s model or the Change Journey Pyramid from Erich R. Buhler’s, one thing is certain: you need to have a vision for your change to guide you. Have a perspective of your ultimate destination is crucial.

Pick a tool and try to apply it, help your teams take ownership of the change, and make sure there is an efficient way to remove the coming obstacles.

Irena P. Krivosheeva